From the 3rd to the 5th April 2024 the British Irish section of the European Group met in Cardiff for a conference on ‘Independence, Abolition and Resistance’. I was really pleased to speak and have drafted this short piece based both on a recording of my talk and some reflections/additions provoked by the brilliant feedback from other participants.

The case for Independence

My starting point was that I support Welsh independence from the United Kingdom. The mainstream arguments, both for and against Welsh independence are set out most clearly in the final report of the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales. Obviously, the terms of independence will determine the outcome. The Commission, despite exploring a relatively conservative model, concluded that Welsh independence was not only viable but had many advantages. I would argue that adopting a more radical vision of Welsh independence, based on developing a more equal and just society, such as that advocated by Undod, would provide even more benefits. The current economic arrangements drain resources out of Wales and organise its society to service the British (English) economy. To make this point I used a map of Wales’s railways – all tracks point to England.

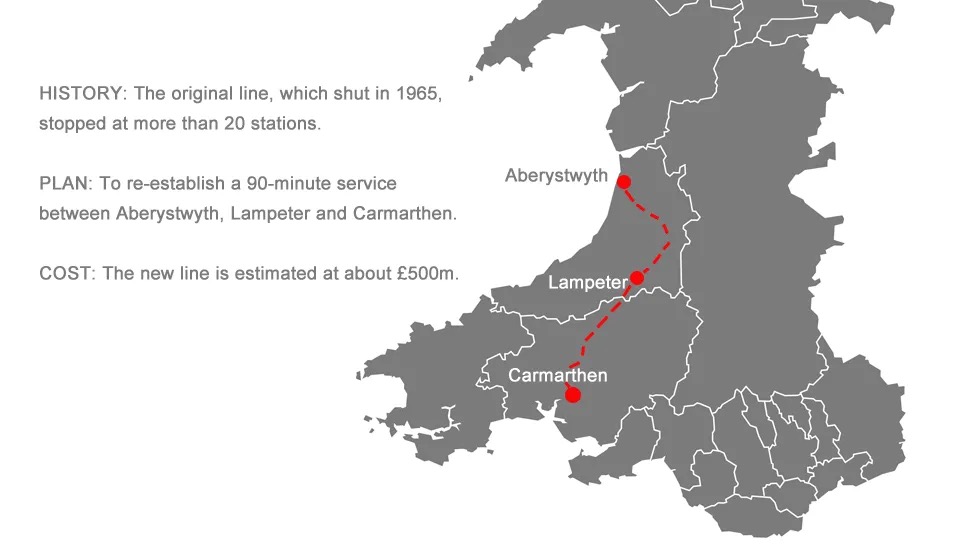

I live between Carmarthen and Aberystwyth, to travel between these two west Wales towns by train requires passing through England. Lampeter, Cardigan and most of west Wales isn’t even on the rail network. Yet HS2 was designated an “England and Wales” project and deemed to represent an investment in Welsh rail. By reallocating the “Welsh” contribution to HS2, possibly as much as £5 Billion, to Wales would allow, among other things to the reopening of the line between Carmarthen and Aberystwyth, estimated to cost around £500 million, or 10% of the Welsh contribution to HS2.

Irrespective of the detailed pros and cons of independence lies important political considerations. On a personal level I agree with Undod’s characteristic of the British state as ‘a fundamentally undemocratic, warmongering and imperial order which exploits the working class, the marginalised and the dispossessed for the benefit of the elites’. It is about time that Britain ceased to exist and Scotland and Ireland also gained their independence.

A brief history of British (and Welsh) criminal justice

I have written previously on how English penal law can be traced back to the slave codes of antiquity. Criminal law was never meant to be fair or just, it was established to maintain an unjust world. In Wales and most of the lands colonised by England/ Britain, indigenous conflict resolutions existed that were restorative in nature. They are not offered as an ideal or as a fully formed alternative but their existence needs acknowledging. In particular we need to recognise that they had developed to sustain the social order of their society. Given that they were often more equal, less hierarchical societies who operated with moral economies characterised by extensive mutual obligation their restorative nature made sense.

Like other parts of the British empire, but much earlier, English legal codes were imposed on Wales. Criminal law functioned to establish and maintain an English order. Over time these adapted to the development of the social structure of Britain (and in particular England) and function to maintain it. Inevitably this has meant a focus on disciplining the working class (particularly youth and non-white people), whilst effectively ignoring the far greater harms perpetuated by the powerful. The way criminal justice reinforces inequality and allows the powerful impunity is illustrated by its response to Grenfell Tower, targeting local working class non white residents whilst holding back on any action on the powerful people responsible.

Unlike Scotland who joined the United Kingdom through an Act of Union, Wales was conquered by military force and subsequently annexed. In Wales the law was used to suppress Welsh culture and Language. Prior to the Norman conquest the Welsh had, according to the historian Martin Johnes, a ‘sense and awareness of a common Welsh history, language and law’. At the end of the thirteenth century, Welsh criminal law was replaced by English criminal law. This was according to Johnes ‘because it saw theft and even violence as a matter between two parties’, capable of being resolved through compensation and other restorative mechanisms. Wales was assimilated into England, but with the Welsh being subjected to both cultural and legal apartheid. An example of this was the Laws in Wales Act 1535 that both required that English was to be the only language used in Welsh courts and barred monoglot Welsh speakers from all public offices. The Act was clear in its intentions, it declared that its aim was to prevent:

the people … using a speech nothing like the natural mother tongue (English) within this Realm … and to extinguish the sinister traditions and customs differing from the laws of this Realm.

London’s parliament passed two Acts of Union in 1536 and 1542-3. The first Act was clear about the status of Wales it was to be ‘for ever from henceforth incorporated, united and annexed to and with this …realm of England’.

However, over time the Welsh, or at least those at the top of Welsh society, increasingly adopted a British identity. Welsh people were active in Britain’s colonial enterprises and Wales benefited from the revenues of slavery and colonialism. Within criminal justice both policies and institutions were exactly the same in Wales as in England. In terms of the wider development of British criminal justice institutions and criminal law these developed by a cross fertilisation of ideas, techniques and personnel across not on the British Isles but throughout the British empire. It is important we recognise this common Britishness which characterises institutions that exist across settler colonies and former British colonies that have been granted independence. For example, as I have argued previously the British police emerged simultaneously in Britain and its colonies, and it is an institution largely unaffected by flag independence. We, therefore, need to recognise that the police in England, Nigeria, Pakistan, Wales are “British” police.

So, when we approach the possibility of Welsh independence, we need to start by recognising that the current criminal law and criminal justice institutions that operate in Wales are all British. Furthermore, they have evolved over centuries to maintain a particular social order based around capitalism and colonialism. The focus of those who will lead the campaign for independence and who are responsible for governing any independent Wales are likely to be concerned with transferring criminal justice in Wales to a Welsh government and not transforming it. A key challenge for abolitionists is to highlight the limitations of such an approach and create awareness of an alternative paradigm. Independence does not need to mean more of the same, with the only change being that it is badged as “Welsh”. This will mean not only challenging the carceral logic that drives the British criminal justice system but also the social structures that require it. It means working to create a more equal, just and inclusive society.

Independence – on whose terms?

The reality is that although the principle of independence will need to be established by the people of Wales in a referendum, the details will subsequently be negotiated. This has been the case of all the former colonies who have gained independence from Britain. The agreements that emerge have ‘implicitly accepted the idea that the legal ideology and norms in forming state formation and the wider political and fiscal system had already been defined and systems put in place within which they were to fit’.[1] Independence was conditional on maintaining the existing economic and social arrangements, which had previously been designed to benefit the coloniser, and these, with their inherent structural inequalities, were institutionalised in a written constitution. A constitution written not by the peoples of the newly independent states, but by colonial officials in London subject to intense lobbying by the corporate interests threatened by decolonisation. Power transferred to local elites who took over the existing arms of the state, including the police, prisons and armed forces – the agencies that embodied the state’s capacity for violence – and used them to both maintain their own privileged position and to protect the very interests for whom the post-colonial settlement was designed. The continuity is illustrated by the fact that the colonial police forces transferred to newly independent states retained their special branches, who played a central role in opposing liberation struggles, and these continued to maintain very close relations with the special branch in Scotland Yard.

For the peoples of the newly independent former British colonies much of colonialism continued, they were still policed by the same (British) police, subject to the same (British) criminal law, and confined in the same (British) prisons. [As an aside, when I invited a speaker to talk about his experience of being a Chaplain in an African prison and he showed a sketch of the design of the prison he had worked at, one of my students declared: ‘but that is exactly the same as Birmingham prison!’] This commitment to colonial penal law meant that whereas in some African nations pre-colonial dispute mechanism had survived, often by moving underground, independence meant that ‘the onslaught against the indigenous cultures and institutions was relentlessly intensified by black neo-colonialists’.[2] In settler colonies such as Australia and New Zealand the criminal justice systems have, after independence, continued targeting indigenous communities and reinforcing settler domination. The history of independence highlights how on its own independence changes little. Flag independence has repeatedly facilitated the continuation of colonial/capitalist relationships.

Has independence abolitionist potential?

In thinking about independence and its potential we need to draw on abolitionist wisdom. Abolitionists are often caricatured as idealists seeking the impractical. We are so indoctrinated to think that police, prisons and the paradigm of criminal justice are natural and essential that moving beyond the carceral state is unimaginable. But abolitionist wisdom sees the potential of a different, more equal and just, society. Creating such a society is only impossible if one believes the current social structure, its inequality and punitive ways of maintaining order are eternal. Abolitionists don’t. We believe a different world is possible and we need, in whatever way we can, to build it. As Mariame Kaba has pointed out, ‘if we keep building the world we want, trying new things, and learning from our mistakes, new possibilities emerge.’[3] If we take the abolitionist understanding of justice articulated by Allegra McLeod, namely that it is ‘an integrated endeavour to prevent harm, intervene in harm, obtain reparations, and transform the conditions in which we live’,[4] then it requires finding ways of responding to harm and conflicts that are based on their resolution. These resolutions need to be based on achieving outcomes that repair, reconcile and heal problematic situations in ways that promote equality, justice and peace for all involved. Part of this will be about returning to the principle of the old Welsh law that conflicts need to be seen as disputes between their participants, not an opportunity for the state to exert its power, allocating blame and inflicting pain. We already resolve most disputes ourselves, without recourse to the police or the criminal law, and we need to expand the situations we do this so that eventually we learn that not only can we live without the police, but that it is better to do so.

Abolitionists are committed to creating a world that is very different from the one we live in. We want a society based on equality and justice, and which offers us all the chance of meeting our full potential. We want to live in a world which does not need police and prisons to function. Welsh independence will not bring that world. It will likely see, as was the case with the independence of British colonies, the social structure and institutional arrangements of Britain replicated. However, independence offers up the opportunity to argue for radical change. The process will raise questions of priorities and provide opportunities for doing things differently. An abolitionist perspective offers the opportunity to engage in these debates and offer ideas to help in creating a truly independent and free Cymru.

Wales has participated in British capitalism and colonialism and consequently it, and its institutions, are characterised by the institutional racism that is embedded in the British state. Despite the long history of Wales’s multi-racial communities the injustices of the criminal justice system in Wales we discussed at the conference fell disproportionately on non-white people. Welsh policing is notoriously racist, and independence alone will just transfer this. Therefore, in arguing for independence it is important to totally reject national chauvinism, racism and intolerance of all kinds. We must instead argue for an open and inclusive Wales. If abolition is ultimately ‘about abolishing the conditions under which prison became the solution to problems’,[5] then independence provides the opportunity to argue for a society in which those social conditions can be abolished. In particular in engaging in the debates about independence’s potential we need to resist attempts to make it more palatable by removing radical demands. We need to head Angela Davis’s advice: “We cannot be moderate.”[6]

Footnotes

[1] Latif, L (2022) ‘The lure of the welfare state following decolonisation in Kenya’ in Imperial Inequalities: The politics of economic governance across European empires, edited by Gurminder K. Bhambra and Julia McClure, Manchester: Manchester University Press (pp. 240-258) p.243.

[2] G.B.N Ayittey (1991) Indigenous African Institutions New York: Transnational Publications p. xxxvi

[3] Kaba, M. (2021) We do this ‘til we free us, Chicago: Haymarket Books, p. 4.

[4] McCleod, A.M. (2019) ‘Envisioning Abolition Democracy’ Harvard Law Review, Vol. 132, pp. 1613-1649 p. 1615

[5] Gilmore, R. W. and Murakawa N. (2020) ‘Covid 19, Decarceration, and Abolition’ Haymarket Books on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hf3f5i9vJNM

[6] Davis, A.Y. (2016) Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundation of a Movement. Chicago: Haymarket Books, p.145